92 Days of Summer

Life lessons from a cigarette-loving, screwdriver-drinking grandma

This week, we celebrated my mom’s birthday. As we pulled up into my parent’s driveway, my husband said what I was thinking: “I almost said, “Grandma’s not here yet.’”

As we scanned the family cars in the drive, my grandmother’s was missing. Known as Grandma Jean — so as not to confuse her among the grandkids with my mom, Grandma — she was always the first to arrive. And even this week, a little more than three months after her death, it was odd that she wasn’t around.

That wasn’t always the case. When she first moved here from Rockford, Illinois, three months before my 13-year-old was born, it was odd that she was around.

When my grandmother was in a medical crisis, I was there. When she wasn’t, the 30-mile distance between us might as well have been a continent.

This quote by Rita Rudner sums her up: “My grandmother was a tough woman. She buried three husbands and two of them were just napping.”

My grandmother, my mom’s mom, was also a tough woman — tough to be very close to.

I was scared of her growing up. It seemed obvious she enjoyed her poodle more than she did me. She didn’t do anything with us or for us. We visited out of obligation, or so it felt in my younger years. I remember her visiting us once in Waxahachie and ordering a screwdriver at the Golden Corral. Who does that? (The realities of growing up in a dry county and irony of my ordering habits as an adult escaped me at that moment.)

She moved to Texas to be closer to all of us (and away from Illinois winters). Although she didn’t seem to adore us, she sure did her cigarettes. She had a harsh Rockford accent, lived in a trailer park, and prepared her entire life for complaining to be an Olympic sport. And she was an awful cook to boot.

But she also made my kids a special Halloween bag of candy every year, grinned and laughed when telling stories about them, and kept up-to-date photo albums for all of her grandchildren. She loved to come to my house and, although critical of most people in her life, thought my kids and I did little wrong.

She’s no grandmother you’d order up, but she was who she was.

In 2009, she was diagnosed with emphysema. This, of course, gave her more to complain about. But it also made her scared and more human than she had appeared to me in all my almost 46 years.

There wasn’t a lot I could do; the burden, of course, mostly fell on my mom. But I visited her in the hospital, held her hand when she cried, connected her with a pulmonologist here in Dallas, and fixed meals for her freezer so she didn’t have to cook. I tried to meet her where she was, which is not my nature. But she was in her 80s. She wasn’t going to change and had a terminal illness.

Within the past year, I hugged her every time I saw her. I told her I loved her, really before I actually did.

So I listened. And I cooked.

And then she got better. And our connection, though softened, went back to where it was. I looked for her car in the driveway on family events. I called her on her birthday. I sent her postcards when we traveled.

This back and forth went on for several years. When she was in a medical crisis, I was there. When she wasn’t, the 30-mile distance between us might as well have been a continent.

Then my mom got sick. She’s on the road to recovery and one of the healthiest people I know, but it stopped us all in our tracks. When I told the kids Grandma was sick, they had little response. It took me a few seconds to realize their confusion. “Not Grandma Jean. Grandma,” I told them.

Instant concern.

Which I got. But I realized they felt the same way about her as I had for all of those years. And still pretty much did. She was a family obligation. Something to check off my list. I hated they felt that way too, but she’d made her bed, I knew.

When mom got sick, my role in my grandmother’s life increased. And I was fine with that. I really was. Nothing about her had changed. She didn’t get my life at all. In many vital ways, we were radically different. I had faith, deep friendships, traveled to third-world countries to build houses. My glass — and not just my wine glass — generally is half full.

I had busy, indulged (in her opinion — and not entirely wrong) kids to raise. She had Westerns to watch and neighbors to spy on from the corners of the heavy curtains in her living room.

My grandmother inadvertently taught me not to write people off and to show love even before you might feel it.

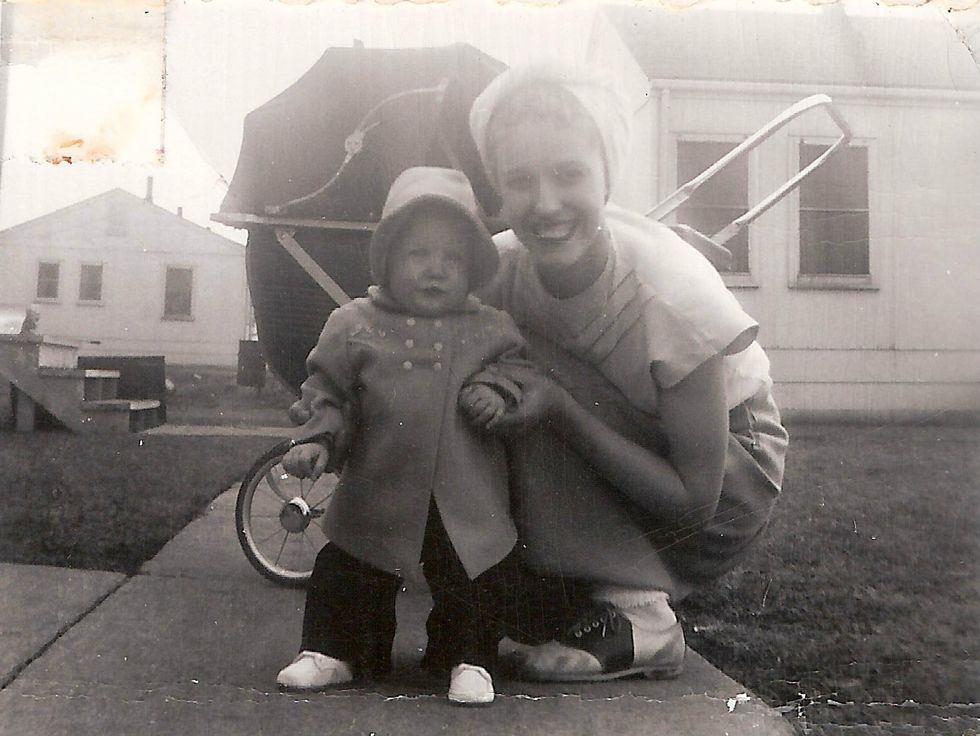

At some point in the last few years, I hugged her. It was awkward. She didn’t seem to know what to do. Within the past year, I hugged her every time I saw her. I told her I loved her, really before I actually did. She never said it back. But one day she had my baby album out for us to go through.

One day this past January, I decided just to go hang out with her on a Saturday. Instead of the usual obligations that took me to visit her, I said we could just do whatever she wanted.

We went to Burger King and Walmart. I’m usually more of an Emeralds to Coconuts and Rusty Taco kinda girl, but whatever. We tried on funny hats, and she laughed and laughed. We went to eat frozen yogurt at Merry Toppins. (Yep, that’s the name). She was almost giddy.

Her health went downhill quickly shortly thereafter. A few days before she died, on a morphine high I’d like to re-create on my deathbed, I walked in to visit. She reached for me to hug me. The hug lasted for a full minute. She said she’d missed me. She said she was so glad to see me. Clearly, she’d just needed some good drugs to take the edge off all these years.

She was my last living grandparent. For a variety of reasons, I didn’t go to the funerals of the other three. And Grandma didn’t want one. Her ashes are scattered up in Illinois.

We’re headed out west this week on a family road trip, going through Arizona and Vegas, two places she loved. I feel a family talk along the way about Grandma and how she inadvertently taught me not to write people off and to show love even before you might feel it.

Because, in the last few months, I did feel it. When I told her I was going to miss her, unexpected tears and all, I meant it. She said, "I know."

Until just a few weeks before she died, she thought she had years to live (suddenly, she’s Mary Sunshine). I thought we at least had the summer.