The Farmer Diaries

Texas farmer shucks the mysteries of growing corn

When people envision a farmer tending crops in a field, it is almost always corn: tall, hardy stalks with long, narrow leaves and tassels on top. Corn is emblematic of farming. Cornstalks covering the countryside form a picturesque backdrop for a tractor, farm house and anything else that completes our notions of idyllic rural life.

But for me, corn has been a source of frustration and discouragement in my attempt to opt out of industrial agriculture and take corn off my grocery store list. Things start out well. The seed is big enough to handle easily and plant in well-spaced rows in spring. The seedlings germinate quickly and grow into plants waist high. But when the spring rains cease and summer begins, my corn fizzles into rows of scraggly stalks tattered by grasshoppers.

Corn is considered an easy crop to grow, so my failure has always been a little embarrassing. Nevertheless, each year I give corn another try.

This year, I did two things differently. First, I added a fertilizer high in nitrogen to the soil. Second, I lined each row of corn with drip irrigation.

Once again this year, I ordered standard, open-pollinated improved golden bantam from Willhite Seed and planted it in mid-April, after the last freeze. As always, I planted in several rows, about 50 feet long.

Corn is "wind-pollinated": The ears where the corn produces corn on the cob grow out from the middle of the stalk. Silk strands flow out from the tips of each ear and must be pollinated from pollen that falls from the tassels that grow out of the top of each stalk. It must be grown densely in a large area.

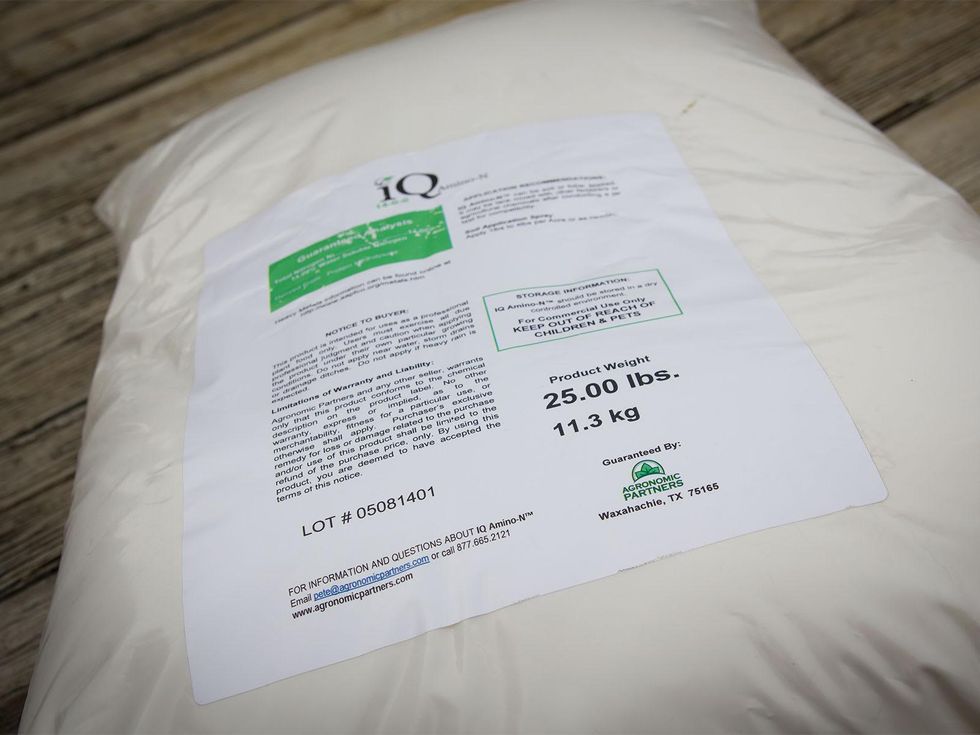

But this year, I did two things differently. First, I added a fertilizer high in nitrogen to the soil along with my usual amendments of soft rock phosphate, Sul-Po-Mag and compost. The fertilizer was called IQ Amino-N, which I picked up as a sample from a sustainable farming company called Agronomic Partners with an office not far from where I farm in Waxahachie.

Unlike my typical soil amendments with a nitrogen value of maybe 4 or 6, the IQ Amino-N had an impressively high value of 14, more suitable for the requirements of corn. Derived from vegetable proteins, the product was consistent with my aim of keeping my farming sustainable and free from chemical fertilizer salts.

Second, I lined each row with drip irrigation, so that I could keep the soil moist no matter how the weather turned out. Frequent showers have given crops a boost this year, but the corn still required supplementation from irrigation.

With these two changes, my cornstalks did not take their usual downward path toward death once June arrived. They kept growing, noticeably taller each day, with a robust resistance to pests. It confirmed for me that pest problems are not so much the cause of poor plant health as much as they are a result of poor plant health.

Once ears formed midway up the stalks and sent out plumes of silk, I knew I had gotten further toward success than ever before. The final proof came at the end of June when I saw that the silk had dried up at the tip of each ear, a sign that the corn was ready to pick.

I grabbed an ear and bent it downward, cracked it off its stalk and tore into the husk. Pulling each layer of husk back, I found even rows of beautifully golden kernels of corn. I popped a kernel with my fingernail to see if it was ready to harvest. The juice inside was a milky liquid, indicating its readiness. A creamy consistency would show it was too late; a clear liquid would show it was too early.

I picked half of the mature ears one day and the rest on the next. I was not surprised when I husked the corn to find worms in about two out of five ears; worms go along with growing corn. Luckily, they'd only eaten the tips.

All I needed to do to salvage the harvest was cut off the damaged end. The affected parts were only an inch long, shortening an 8-inch ear to 7. The kernels at the tip are often immature, so the loss was minimal. The worms' presence was far from what could be described as an infestation.

Corn sugars begin to turn to starch as soon as they're harvested, and therefore corn loses its sweetness if not cooked or prepared for storage immediately. The first day I picked corn, I ate it as corn on the cob that night.

The flavor was more intense than what I buy from the store; the texture of the kernels was plump yet crunchy. I'm not the first to say it, but nothing bought at the market ever tastes as delicious as food that's fresh from the garden.

Altogether, I'm satisfied with my new success with corn. It offers more motivation to never give up on a challenging task, even when I've failed at it — repeatedly — before.

Harwood District Olympics bar crawl. Harwood District

Harwood District Olympics bar crawl. Harwood District