The Farmer Diaries

Texas farmer discovers 8-legged ally in the war against grasshoppers

In my ninth grade biology class at Waxahachie High School, we learned about how living organisms can adapt to adverse conditions and survive. The grasshopper was the example we studied.

Prone to devouring all vegetation in their paths, grasshoppers cause huge crop losses throughout the world. Because of their hard exoskeletons, they aren’t easily crushed, and they group together by the millions to form a swarm that can move onto a field and strip it of everything green before moving on.

Then, in the early 1900s, it seemed that mankind finally got the upper hand with the development of synthetic insecticides, which could gas a swarm of grasshoppers and save the crops from invasion. If that had been all there was to it, we’d now only study grasshoppers as a famine-causing plague that mankind eradicated from the planet.

I have witnessed a slow decline in the grasshopper population in the last several years. But this sudden disappearance has perplexed me.

But there was more to this story, because some grasshoppers either had or built up a resistance to the chemicals. In turn, their offspring were a little more resistant, and so on, until millions of insects would again populate the fields, laughing at all of our futile attempts to gas them out of existence.

Eventually the grasshopper evolved from an occasional pest to a persistent summertime problem. Every year a new application of insecticides was required keep them under control, because their natural predators were less resilient.

In the mid-1970s, my family bought a spot of land and built a house on the 20 acres right after the previous owners made their final harvest. The corn, wheat, sorghum and cotton grew around us, and frequent crop dusters flew over, spraying tons of poisons that made the air thick with an acrid odor. Still, the grasshoppers thrived.

There was a cloud of grasshoppers wherever I walked; sometimes they smacked me right in the eye. This was true every summer, from my childhood to my teens. They ruined the trees we planted and the landscaping bushes, and they made growing food crops a chore.

When I moved back to the land after college and tried out my first garden out after a long hiatus, they ate everything — even the onions, which are usually immune to grasshoppers. It was the same year over year, until now.

So why, in the summer of 2015, have they nearly all disappeared? When I walk out into my field to tend my melon crop, it startles me when a single grasshopper jumps out from the weeds. My tomatoes, which by now should be ragged and tattered from the grasshopper onslaught, are lush and green.

Zinnias are untouched, and trees are thriving. Grasshoppers haven’t been an issue anywhere on the land.

When I took a closer look, I discovered that the spider was feeding. Clutched in four of her long eight legs was an adult grasshopper she had caught.

I know that I saw their fry this spring, just as always. But something happened between then and now that has wiped them out.

It wasn’t the rain. Other parts of the state came out of the drought too, and they still have grasshoppers; a swarm of beetles and grasshoppers even appeared on weather radar last week over Knox County, between Dallas and Lubbock. There also have been wet years before this one, and the grasshoppers were just as bad then.

I have witnessed a slow decline in the grasshopper population in the last several years as families of skunks and flocks of birds have taken down their numbers. But this sudden disappearance has perplexed me.

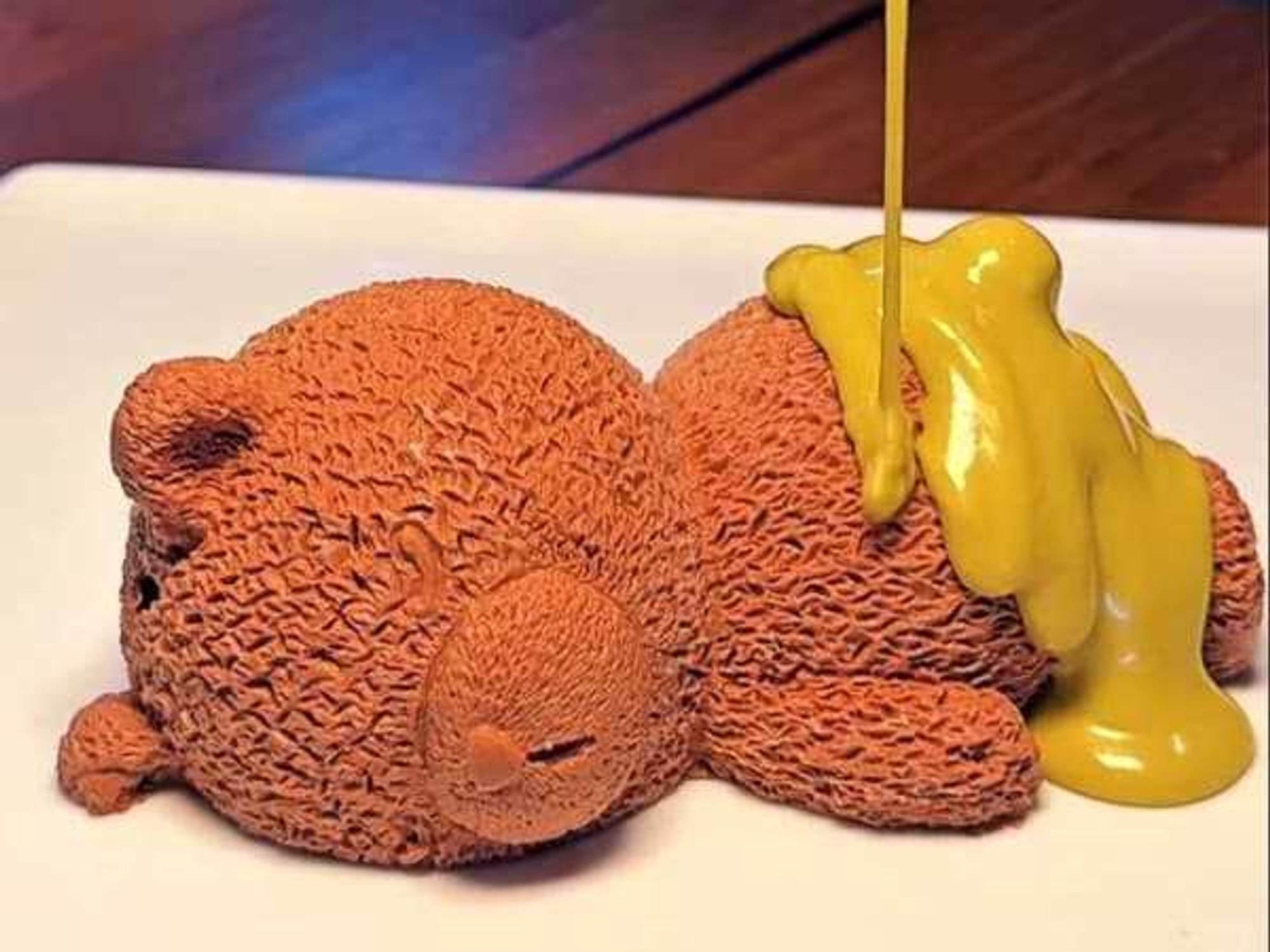

Little by little, a few clues began to show up, like when I knelt down beside a bucket so that I could fill it up with water from a spigot in the middle of our melon field. In the bunch of weeds around the hydrant, I spotted a wolf spider, about the size of a baby’s hand, strangely clutching onto some leaves.

I’d never seen one perched like that before. When I took a closer look, I discovered that the spider wasn’t just sunning herself and enjoying the day; she was feeding. Clutched in four of her long eight legs was an adult grasshopper she had caught.

Soon afterward, as I sat on a picnic table under a tree in my front yard, I saw something move in the glow of a string of party lights I had just strung up — it was a spider the size of a mouse. She sat there with me for several minutes, either admiring the multicolored lights or hoping to exploit them to catch prey.

From then on, everywhere I looked there were spiders: wolf spiders, orb weavers, green lynx spiders, jumping spiders — you name it. When I walk around at night with my Ryobi spotlight, I can see a world where spiders dominate.

Up in the trees there are countless nocturnal spiders that spin their webs as the sun goes down, sending out long guy-wires that can span 30 feet between two trees and building their net right in the center, sometimes up 20 feet high. They’re so numerous that their peach-colored bodies make the trees look as if they’re decorated for Christmas.

Spiders have built webs at every entry to my house, at my butterfly feeder — wherever there’s something to which their webs can cling.

Less than in the past but still making a showing are the common black and yellow garden spiders with their zigzag patterns in the center of their webs. From the tip of one leg to the other, they span about the diameter of a baseball, and their tough webs trap grasshoppers like they were designed for the purpose.

Spiders have built webs at every entry to my house, at my butterfly feeder — wherever there’s something to which their webs can cling.

Under leaves and flowers, green lynxes and all colors of jumping spiders are having a good year. They’re not large enough to catch adult ’hoppers, but they’re thriving numbers bolster my speculation that the reason for the pest decline on the property is that 2015 is the year of the spider here.

Perhaps the strongest evidence that spiders have halted the grasshoppers is what my wife and I discovered one moonlit night when we sat on a farm trailer out in the field. I had my spotlight, and I thought of showing her how I used to find spiders when I was a kid, by holding a flashlight at face level and shining the beam out in the field toward the ground until I found a tiny reflection.

If I kept the light shining back at me and walked toward it, I’d find that it was the reflection in the eyes of a spider looking at the light. It was just a curiosity, something I happened upon when I was about 10.

But that night, as I shined the light out in the field, the grass glistened as if it were coated in fresh morning dew — only it was dry. Those countless reflections were all the reflections in the eyes of the wolf spiders.

And those were just the ones that turned to look at the light. How many more were looking away I can’t say. They don’t spin webs. They roam on the ground and catch prey like a cat does a mouse, and they were everywhere.

If there are other reasons for this property’s being cured of its grasshopper plague this year, I don’t know what they could be. But when you see a land thick with grasshopper killers, it’s not a stretch to reach the conclusion that they’re responsible.

Back in the early 1900s, when chemicals insecticides were developed for agriculture, what would have happened if someone had said, “No, instead of poisoning the land to rid it of pests, why don’t we find a way to bolster the spider population?”