Appreciation

Dammit, Roger Ebert! Did you have to cut back on reviewing this much?

When I first heard the news Thursday that Roger Ebert had died, I must admit my first thought was to send him an email: “Geez, Roger. I know you said the other day you were cutting back on your reviewing. But isn’t this a bit, well, extreme?”

Please don’t misunderstand. I do not mean to make light of my friend’s passing. But I am certain that he would appreciate the joke.

Just as Roger himself found humor in the situation when I told him, during his earliest and seemingly victorious battles with the cancer that would eventually defeat him, that I had lit two candles for him at my neighborhood church as a prayer for his speedy recovery.

As I have often told friends, colleagues and students, the greatest thing about Roger’s reviews was — and still are — their blunt-spoken, open-hearted directness.

“Thanks, Joe,” he replied. “But you know, the candles work only if you actually pay for them.”

To which I replied: “Hey, I paid $2. The last time a $2 bet paid off for me like that, I was at the racetrack.”

A while later, on Christmas Day 2009, while I was waging my own battle with The Big C, I told Roger that I had lit another candle for him, so he was good for at least another year. And, yes, I did pay for it.

He was not impressed: “If you don't pay, I'm good for two years, at 30 percent interest.”

So I responded, “Really? Damn, wish I'd known that — 'cause I lit one for myself as well.” (BTW: As of Wednesday, I will be halfway through the radiation treatments. But I don't yet glow in the dark.)

As usual, Roger had the last word. “Glowing can be a convenience.”

And so it went. Roger was one of the first of the very few people with whom I shared the bad news when I received my prostate cancer diagnosis. And he was unfailingly gracious and reassuring as we swapped emails during my therapy. The day I endured my final irradiation to eradicate the cancel cells, Roger congratulated me thusly: “Hooray! Billions of the little buggers dead!”

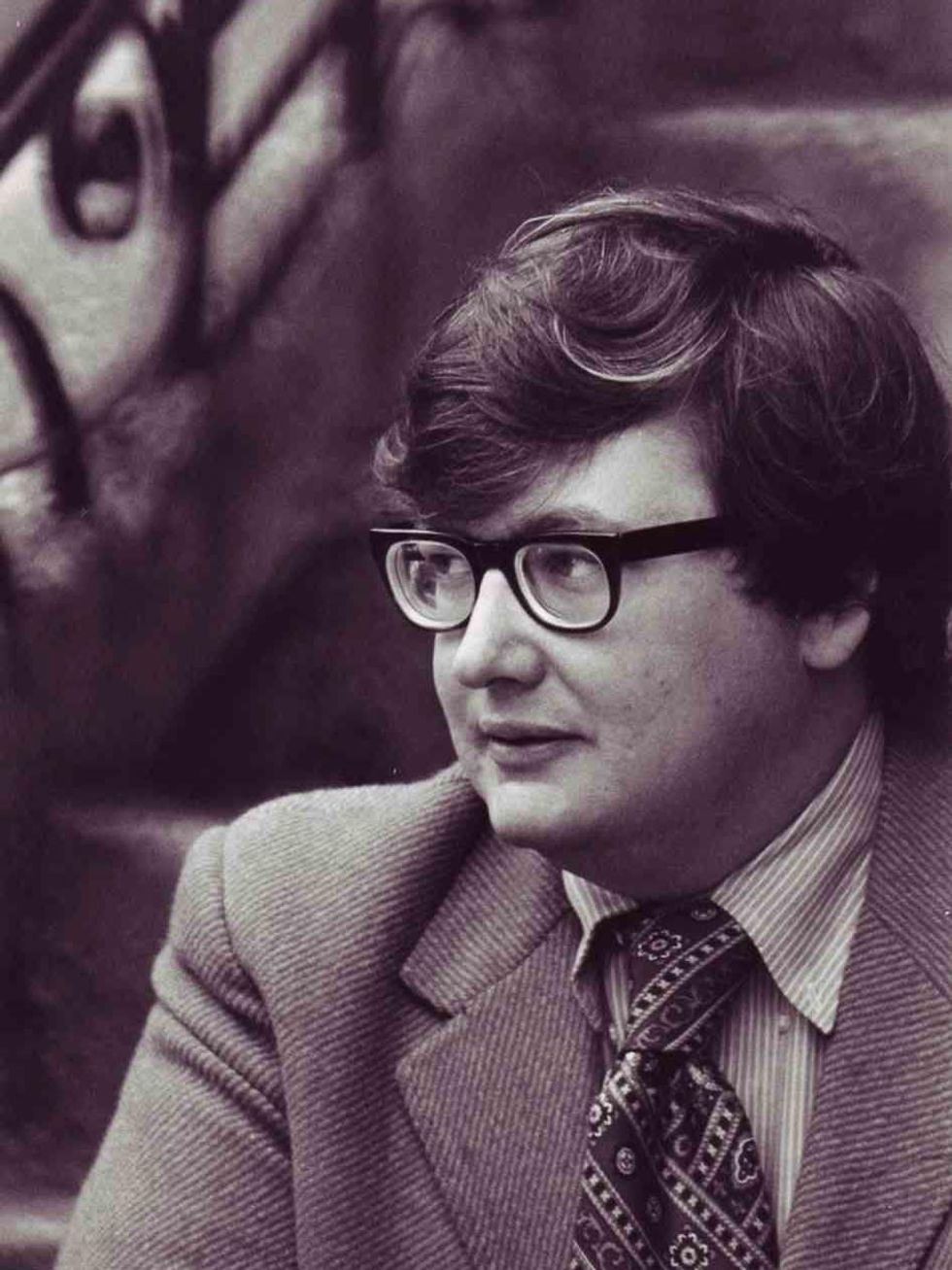

Mind you, we were friends and colleagues long before each of us received rude reminders of our mortality. I first met Roger back during my salad days in the early ‘80s at the Dallas Morning News, when he frequently appeared at the USA Film Festival in Big D to introduce films.

He already was a superstar critic, thanks to the innovative and influential TV show showcasing him, Gene Siskel and their thumbs, and I was a lowly staff writer for the paper’s Arts & Entertainment department. But he treated me as nothing less than an equal when I interviewed him and eagerly invited my own opinions and predictions as we discussed the then-burgeoning home-video revolution. (We both agreed that B-movies and exploitation fare would eventually bypass theatrical distribution altogether and reach audiences as Beta and VHS products.)

Years later, while I was film critic for the Houston Post, we would share knowing smiles (and, yes, thumbs-up) backstage at the Academy Awards, because we both were using the digital marvel of the era, the Radio Shack TRS-80 laptop (not entirely affectionately known as the “Trash 80”). It was around this time that Roger gave me a few shout-outs in his 1987 book about covering the Cannes Film Festival — Two Weeks in the Midday Sun — including a mention or two about our misadventures while filing with our Trash-80s. (The French phone system was, how you say, less than cooperative.)

And speaking of Cannes, I fondly recall a long lunch on the beach with Roger and Bob Woodward the year Wired — the flawed but fascinating movie based on Woodward’s controversial biography of John Belushi — premiered at the Palais du Festival.

As I would later describe part of the conversation:

Ebert vividly recalls the days when John Belushi was a [Chicago] celebrity, a main attraction at the Second City comedy club. Woodward listens intently as Ebert speaks.

“I used to drink with him,” Ebert says. “One thing that I question in the movie is — and I know probably why these choices were made — Belushi says he's a social drinker. Well, Belushi was a drunk who turned to drugs to control his alcoholism.”

Ebert says Belushi opened his after-hours Blues Bar because he was thrown out of other after-hours clubs in Chicago. “And he was a Jack Daniels kind of drinker — the bottle right to the mouth ... He was an alcoholic long before he tried drugs.”

“I'm embarrassed to say I didn't know that,” Woodward says.

“I'll never forget one night,'' says Ebert. ''It was in the Blues Bar, during the filming of The Blues Brothers. Belushi was bartending, and he was drinking Jack Daniels out of the bottle. And at one point, he was very drunk, and he was trying to kind of shout or act himself into sobriety. And he put his hand on either side of the area behind the bar where they have the ice, where they scoop out the ice — and he just stuck his whole head in there, in the ice, for about 30 seconds. And then he came up, shouting 'Whaaaa-ahhhhh!'

“This is one of the seven or eight danger signals of alcoholism.”

Woodward shakes his head, in the manner of someone who's hearing his worst suspicions confirmed.

If you read Roger’s reviews carefully enough over an extended period, you could spot allusions to his own status as a recovering alcoholic. And even if you didn’t read so carefully — well, sometimes, he’d just come out and tell you about it. Much like he noted that since both his mother and his father died of lung cancer, he was especially interested in the anti-Big Tobacco theme of Michael Mann’s The Insider : “The Insider had a greater impact on me than All the President’s Men, because you know what? Watergate didn’t kill my parents. Cigarettes did.”

As I have often told friends, colleagues and students, the greatest thing about Roger’s reviews was — and still are — their blunt-spoken, open-hearted directness. Just as Francois Truffaut used to proselytize for a cinema that spoke directly to audiences — “More personal than an individual and autobiographical novel, like a confession, or a diary!” — Roger wrote reviews in the manner of someone addressing an acquaintance in a cafe, describing his passion (or lack of passion) for this or that film without pretense or self-censure, speaking from the heart without artifice or self-indulgence.

Mind you, his extemporaneousness was more apparent than real: His reviews are rich with insights that come only after careful consideration, and his entertaining style is clearly fueled by nimble intelligence and a strong sense of film history. He was, in short, a great writer who wrote best about what he loved most. (Remember, he was the first — and for several years the only — film critic to claim a Pulitzer Prize.) And even when cancer treatments denied him the ability to speak, he continued to write — prodigiously, obsessively — with a gleeful industriousness that could make his contemporaries look like just so many slackers.

Thanks in large part to Roger and Gene Siskel, film criticism enjoyed a boom period in the United States stretching from the late ’70s to the mid-’90s, as their success in reaching and intriguing the masses played a substantial role in influencing the bean-counters and decision-makers to hire their own film critics at countless print and broadcast outlets.

And even after all too many of those film critics were bought out, laid off or otherwise discarded during the era of post-Internet downsizing, Roger continued to be uniquely influential as a reliable source, a respected tastemaker — and, yes, a brand name.

A few years back, just before the publication of my first book, my publisher told me he was sending a copy of the galleys to Roger, in the hope of obtaining a favorable comment that could be exploited in advertising. I emailed Roger to warn him what was coming and to express my kinda-sorta apology, because I knew he’d be getting the package just before he left for Cannes and would be terribly busy with preparations, and I would understand if ...

My publisher called with the good news a few days later. Roger had taken the time to read the galleys and provide a few words of praise. So they were ditching the original cover design and coming up with something new so they could print what Roger had to say. I was overjoyed, naturally, but a tad bit worried: Would this last-minute redesign be a problem?

“You don’t understand,” my publisher told me in the tone of someone explaining something as basic as gravity to a small child. “You’ve got the freakin’ holy grail of blurbs here! This is Roger Ebert!”

Yes, it was Roger. The same guy I emailed last Christmas, to tell him that, yes, I had lit another candle for him. And one for me.

His succinct response: “Stayin’ alive!”

A confession: Each time Roger referred to me in print as a fellow critic — or, better still, as a friend — I felt deliriously, unreasonably happy, as though I had been allowed inside an inner circle. And when he included me in the list of film critics whose childhood homes he wanted to feature in a photo slideshow, I was not merely honored, I felt blessed. Right now, I feel as devastated I did the day Francois Truffaut died.

But I’m still a little peeved: Geez, Roger, did you really have to cut back by this much?