TEDxSMU Teasers

TEDxSMU speaker Michael Sorrell takes urban college from campus to community

Paul Quinn College president Michael Sorrell didn’t plan on a career in higher education. The Chicago-born, Duke-educated lawyer and public affairs consultant enjoyed a successful career that took him as far as the White House during the Clinton Administration.

When the historically black college in South Dallas asked Sorrell to step in as interim president in 2007, it was 30 days away from bankruptcy and in the process of losing its academic accreditation.

But in this crisis Sorrell saw an opportunity to build something great for an underserved community. Although he readily admits he knew very little about running a college, he was confident that building a strong culture around hard work and innovation would ultimately lead to success.

“Higher education institutions should engage in the issues of the communities they serve,” Sorrell says.

Six years later, Paul Quinn College has reinvented itself. Under Sorrell’s leadership, the school is financially solvent, fully accredited and has a growing student body.

Bold moves such as disbanding the football team to turn the field into an urban farm and standing up to City Hall during the proposed expansion of McCommas Bluff Landfill have made headlines. Heck, even Bill Cosby noticed the epic turnaround of Paul Quinn College and spoke at the graduation commencement last spring.

President Sorrell discusses his vision of the “new urban college model” on Saturday, October 19, at TEDxSMU. We spoke with him about his big plans for the small college and how his vision goes far beyond the campus.

CultureMap: When you started at Paul Quinn College, it was on the verge of bankruptcy and about to lose its accreditation. What was the first step you took to solving the massive problems facing the university?

Michael Sorrell: The first thing I said to folks when I came in was we need to set a standard and give people something to believe in. We set a goal: We are going to become one of America’s great small colleges.

Then we established a work ethic for getting there. I made it clear that it wasn’t going to be easy. In fact, it’s going to be the hardest thing you’ve ever done. Telling people we are going to become one of America’s great small colleges when the worry was can we even stay alive gives you a good sense of who’s crazy enough to stick with you.

“I don’t need to teach [our students] to get a job; I need to teach them to create jobs.”

Then I took a hard look and was transparent with folks: This is who we are, this is where we are, this is our financial situation and here are the things that are inconsistent with our stated goal. One of these things was football, so the first week I cut the football program.

CM: Your TEDx talk will focus on the “new urban college model.” What is the old urban college model, and how are you reinventing it?

MS: One of the problems is that higher education has allowed itself to be defined in a very narrow sense. Part of that is earned by folks pursuing selfish research or institutional agendas that exclude the community surrounding the institutions.

Doing so alienates the community, alienates potential students and has contributed to higher education’s reputational issues. I’m saying that higher education [institutions] should engage in the issues of the communities they serve.

They should use their student talent and the organizational resources to transform their students into entrepreneurs. Not entrepreneurs in the naked, capitalistic sense, but use entrepreneurial thought and action to solve problems.

I’ve come up with a model called the “new urban college model” that uses experiential learning and entrepreneurship to take students from under-resourced communities and transform them into the folks who solve the problems of those communities. I think urban colleges would be remiss for not embracing this new model.

I purposely do not use the term “historically black college” or “minority servicing institution.” I don’t think it is just a black problem or a Hispanic problem. What I’m saying is that if you are in an urban environment and you service under-resourced communities, this formula should still be applied.

CM: So the new urban college has a higher purpose of serving and bettering the community. In your opinion, what is the greatest challenge facing South Dallas today?

MS: We’re making our plans not just based on what we see in our immediate backyard, but view our community as the global under-resourced communities of individuals who suffer from the same economic perils.

“Ignore us at your own peril. This is going to work, and it’s working for us.”

We have to deal the food deserts. Food insecurity is embarrassing. We’re 10 minutes from downtown Dallas, and we’re in a food desert? How can that be? If someone asks where we want to go to lunch, there is nothing here.

There are no coffee shops, no bookstores, nothing. And corporations tell you that people in our community don’t fit their customer’s demographics. I can’t sit here and pretend that is okay.

CM: Where did you look for inspiration for this new model?

MS: Some of what we’re doing is an adaptation of the “work college model.” The difference is that the work college model primarily focuses upon rural areas. I think we can apply this model to an urban area with a twist.

Let’s provide a framework and business structure to help students become part of the solution. You take the work college, then look at schools like Stanford and MIT and what they’ve done around entrepreneurship and combine it with our mission of serving the community.

We bring this model in, using students who would never have access to those types of institutions. Then all of a sudden you get some very exciting possibilities. There are more of those kids than anyone.

I want our students to be able to adapt to everything their life is going to throw at them. I don’t need to teach them to get a job; I need to teach them to create jobs.

CM: How can other colleges learn from what you’ve done at Paul Quinn?

MS: There are some colleges acknowledging they need to do something radically different. One of the things I learned about higher education is they can be a bit elitist regarding where they take their cues.

It might seem odd to some people that these ideas are coming from the place that they are. We can spend time haggling that this theory didn’t come from what you can consider a blue blood institution, but most of the urban colleges aren’t blue blood, anyway.

Ignore us at your own peril. This is going to work, and it’s working for us. My response to those folks is that innovation comes from where it comes from.

CM: Where do you see Paul Quinn in five years?

MS: We will have a grocery store, our online program will be thriving and we will have served irrefutable notice that we are on the path to becoming one of America’s great small colleges.

I don’t think you should start college online, but a hybrid model is excellent, and we are looking at it from the standpoint of adult degree completion in some very target areas. Some disciplines lend themselves very well to online learning. We have partnered with Kaplan and will be offering our adult degree program very soon.

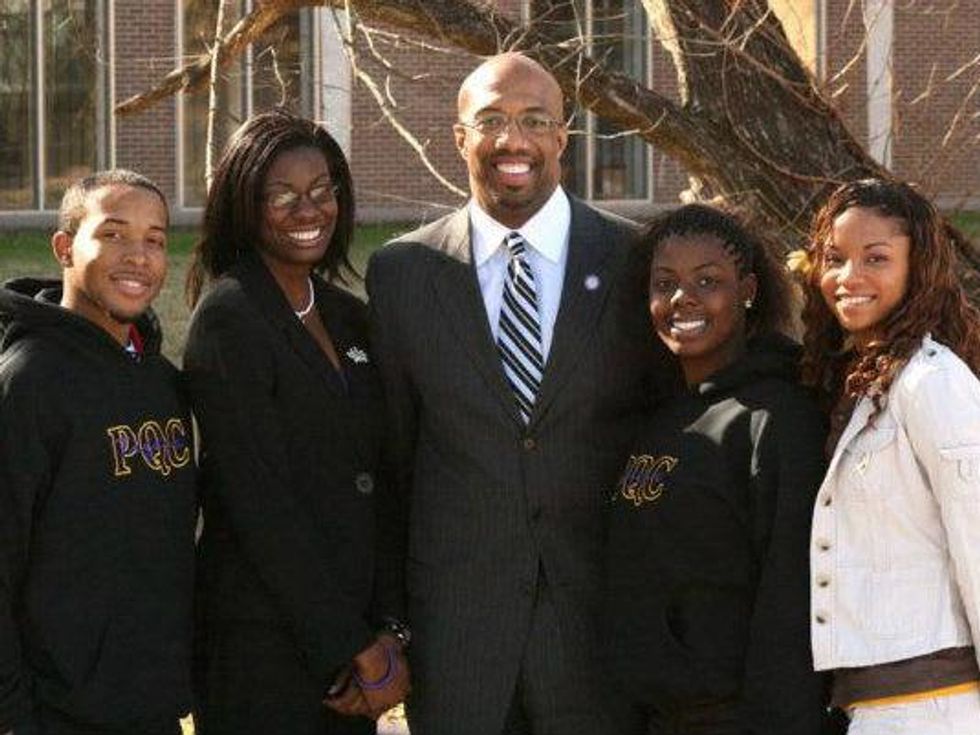

Paul Quinn College president Michael Sorrell, pictured here with students, speaks about the "new urban college model" at TEDxSMU October 19.