Woody Allen Winner

Cate Blanchett shines in title role of shocking and mysterious Blue Jasmine

There is more than a hint of Tennessee Williams’ Blanche DuBois in the title character Cate Blanchett plays so precisely and affectingly in Blue Jasmine (at Cinemark West Plano), Woody Allen’s exceptionally fine new film about the slow-motion implosion of a woman who has exiled herself to a state of denial.

Much like the bruised southern belle of Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, Jasmine is a refined elitist who must swallow her pride after an economic setback and move in with her earthy and inelegant sister. Also like Blanche, she meticulously disguises — or, perhaps more accurately, willfully forgets — the more unpleasant details of her checkered past, in the hope of securing a prospective husband.

Cate Blanchett can’t help but overshadow everyone else on screen. Jasmine wouldn’t have it any other way.

And, perhaps most important, Jasmine, like Blanche, ultimately finds herself sorely ill-equipped to deal with harsh realities without the comfort and support of her self-deluding fantasies.

Don’t worry: The last sentence is not quite the spoiler it may appear. Indeed, the final scenes — along with quite a few earlier ones in Blue Jasmine — are genuinely surprising. So much so, in fact, that they likely will cause you to view the entire narrative in a new light as you replay the movie in your mind long after the final credits roll.

Working in a far more serious vein than he has in such recent efforts as his Oscar-winning Midnight in Paris — but sustaining his winning streak when it comes to writing strong roles for women — Allen stealthily inserts elements of a detective story into his drama about Jasmine’s emotional and psychological free-fall.

There’s a jarring revelation at around the half-hour mark that darkens what has been, up to that point, the film’s relatively light mood. Although Blue Jasmine never fully descends into the depths of ponderously morose seriousness charted by Allen’s Interiors and September, that revelation signals a fair warning that we should not assume, no matter how bright things fleetingly appear, that a happy ending is guaranteed for everybody — or anybody.

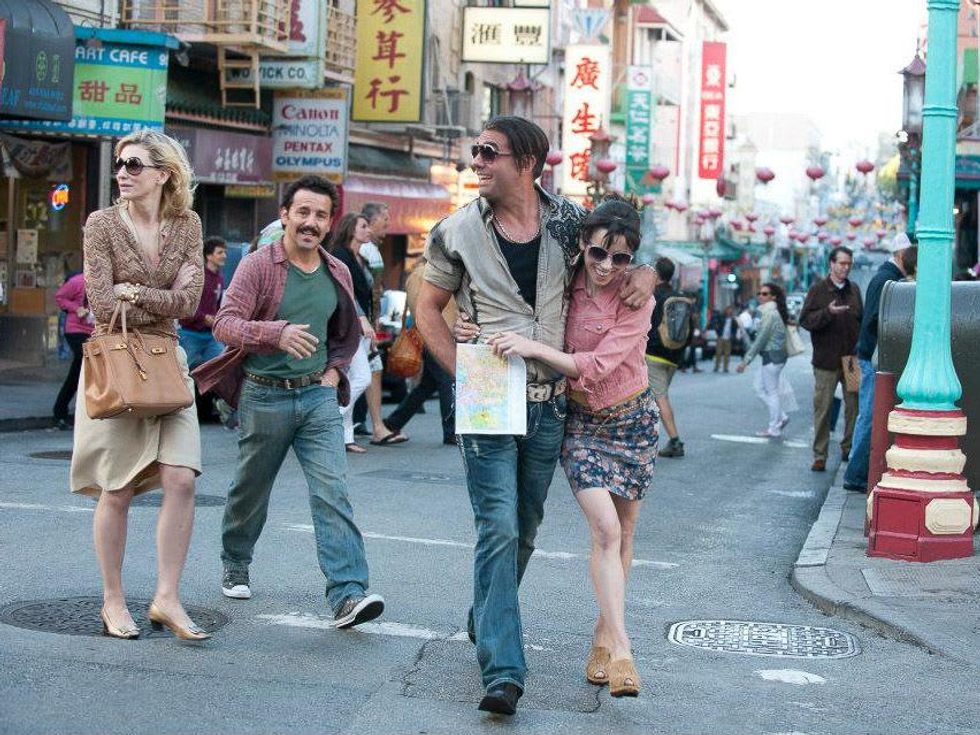

Jasmine flees New York, where she once enjoyed the high life, and heads to San Francisco, where she seeks sanctuary in the cramped apartment of Ginger (Sally Hawkins), her divorced sister. Jasmine’s smooth-talking investment-banker husband, Hal (Alec Baldwin) has been arrested for his Bernie Madoff-style bilking of unwary investors.

Strictly speaking, Ginger and Jasmine were separately adopted by the same parents — and the dissimilarity of their lifestyles is much remarked-upon. Although Jasmine married extremely well — or so she thought — and savored years of nonstop luxury that left her with an industrial-strength sense of entitlement, Ginger has never really tried to elevate herself above blue-collar status.

This film is, on one level, a detective story, with the audience cast in the role of inquisitive investigator.

She works in a grocery store and shares her cramped apartment with two chubby and undisciplined young sons. She dates a rowdy garage mechanic, Chili (Bobby Cannavale), whom Jasmine views with the sort of disdain Blanche DuBois reserved for Stanley Kowalski.

Ginger is a good soul, but she can’t entirely disagree with her brutish ex-husband, Augie (Andrew Dice Clay), that Jasmine sabotaged their future, and their marriage, when she encouraged Augie to invest his serendipitous lottery winnings in one of Hal’s shady investment schemes.

Still, she readily agrees to make room in her already overcrowded apartment for Jasmine, and even puts up with her sister’s condescending attitude, because that’s the sort of generous person Ginger is.

In short, she’s nothing at all like Jasmine. Well, nothing at all if you don’t count evidencing distressingly similar cluelessness when it comes to choosing men.

A mystery in a movie

Early on, we’re told that Jasmine suffered a nervous breakdown at some point between her husband’s arrest and her purchase of a plane ticket. Despite her residual psychological vulnerability — or maybe because of it — she is determined to reinvent herself in her new surroundings or, failing that, find a husband who can support her in the manner she’s absolutely certain she deserves.

Almost miraculously, she gets a shot at Option No. 2 when she meets Dwight (Peter Sarsgaard), a wealthy and politically ambitious charmer, at a dinner party. She thinks he’s almost too good to be true. Trouble is, he feels pretty much the same way about her. Disappointment awaits.

Blanchett comes to Blue Jasmine after playing Blanche DuBois to great acclaim in a 2009 New York stage production of A Streetcar Named Desire, which, judging from her performance here, obviously qualified as terrific on-the-job training. She underscores and enhances every element of Jasmine that Allen has, ahem, borrowed from Blanche.

But Blanchett also builds upon that — goes beyond it, really — to give a full-bodied, flat-out brilliant performance of a desperately duplicitous woman who appears to be avoiding another meltdown only through sheer force of will, and whose self-absorption devolves into something not unlike sociopathy.

Blanchett makes Jasmine’s self-justifying riffs and rants mesmerizingly horrifying — at times, she’s a living and breathing train wreck from which you cannot avert your gaze — and Allen subtly amps the fury of her outbursts by presenting them in continuous takes, rather than cutting away for reaction shots of secondary characters.

To be sure, the supporting players are uniformly excellent — Sarsgaard is every bit as effectively sympathetic here as he is impressively appalling in Lovelace — and they make invaluable contributions to the movie’s cumulative impact. But Blanchett can’t help but overshadow everyone else on screen. Jasmine wouldn’t have it any other way.

It should be noted, by the way, that Blanchett is just as riveting when she dials it down to seven, and sometimes even five, especially during the sporadic flashbacks that detail those halcyon days in New York when Jasmine felt she had not a care in the world.

Allen shrewdly cuts back and forth between past and present throughout Blue Jasmine, so that we only gradually discern motives and meanings behind Jasmine’s current state. As I said earlier: This film is, on one level, a detective story, with the audience cast in the role of inquisitive investigator.

And rest assured, like all good detective stories, it provides a satisfying solution to its central mystery.