The Farmer Diaries

Texas' Willhite Seed Company overcomes setbacks in win for small farmers

A small Texas seed company nearly felled by a devastating disease is springing back with a creative solution aimed to help the small farmer.

Willhite Seed Company announced last fall that, after nearly a century in business, it would shut down due to bacterial fruit blotch (BFB), a disease that has taken an economic toll on fruit producers for several decades.

BFB is a disease that forms dark, dead spots in affected fruit, predominately watermelons, rendering the fruit inedible. It's spread by contaminated seed from melon crops and wild cucurbits, making containment difficult. Hot, wet conditions in a field or greenhouse increase the likelihood of BFB spreading.

Wilhite's contribution to the sustainable agriculture movement is invaluable, especially as a source of local and affordable bulk seed.

All producers of pumpkin and melon seed are at risk. The disease has been detected in 11 states, and no methods to stop the spread of the disease have been discovered.

Willhite owner Robyn Coffey announced the impending closure in a letter sent to customers last fall. "Many of you are familiar with bacterial fruit blotch, and the burden it has placed on the watermelon industry," she wrote. "Even with signed legal release forms required with the purchase of watermelon seed, Willhite has been left unprotected from costly liabilities incurred."

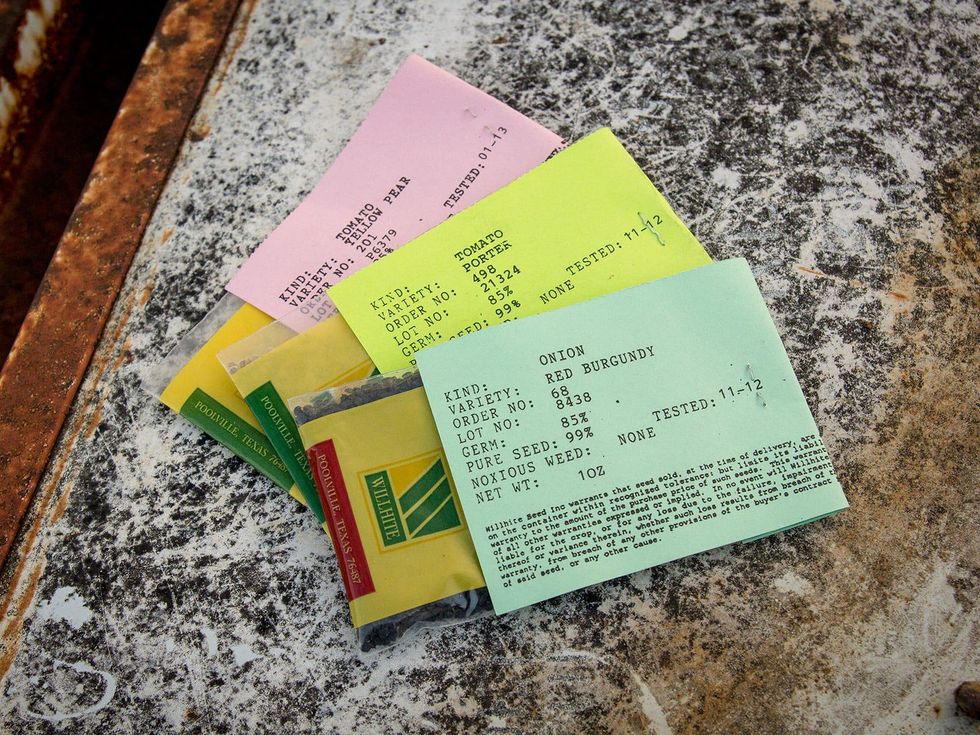

The loss of Willhite would have dealt a major blow to small-scale growers. Willhite is an ideal resource to the specialty farmer working on 10 acres of cantaloupes, or a multi-crop farmer producing a whole gamut of fruits and vegetables — beans, beets, carrots, eggplants, rutabagas and tomatoes — you'd expect to find at a farmers market.

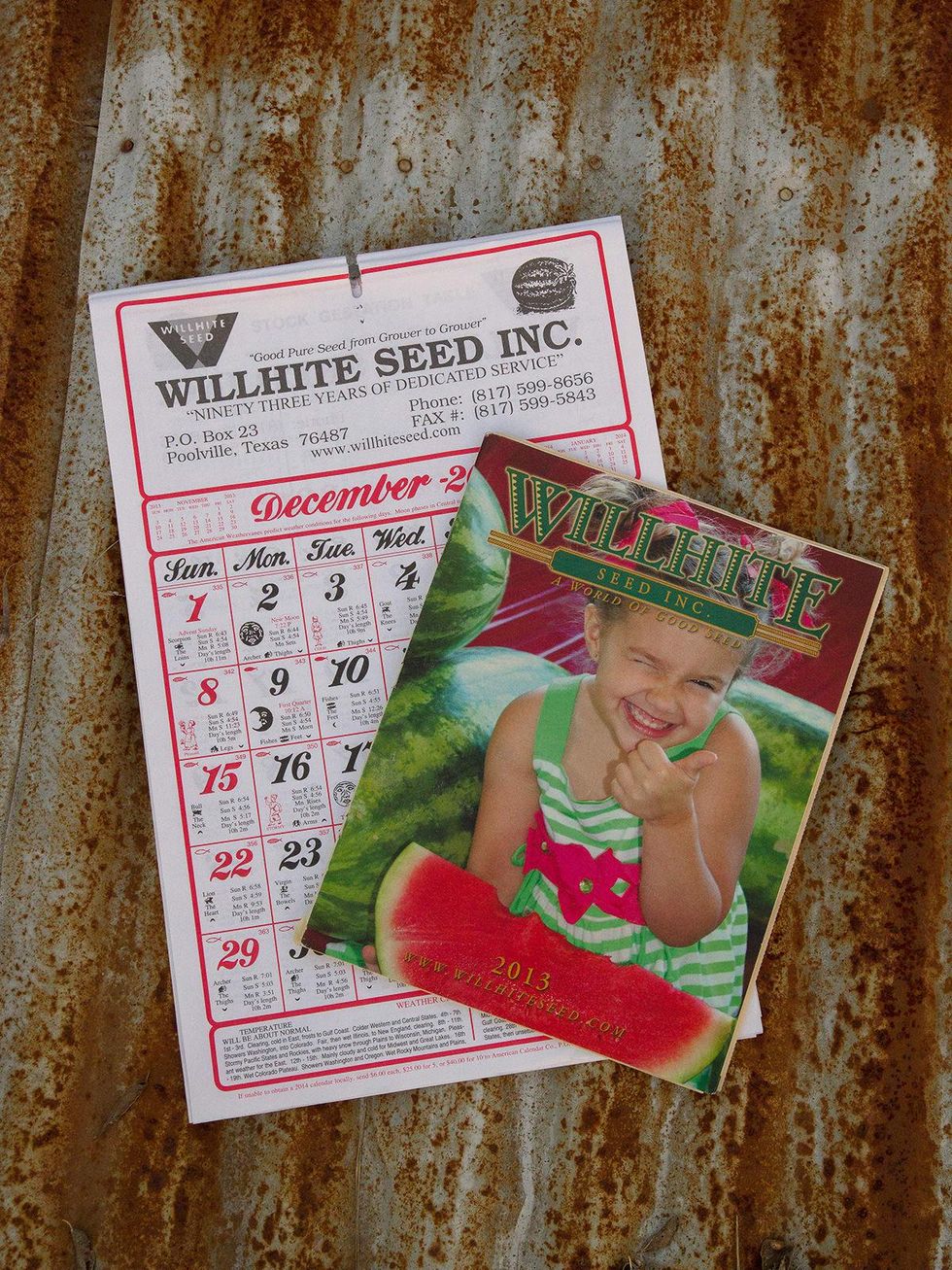

But Coffey has since devised a solution: Willhite will continue to sell seed to home gardeners and small specialty growers but not to larger commercial watermelon growers more likely to initiate litigation. And in a cost-cutting move, the company will also cease production of its annual catalog.

"All orders will be taken online or by phone," said office manager Carol Clark. "We'll still send out our calendar, but last year's catalog, which was our 90th year to print one, was our last."

Willhite's contribution to the sustainable agriculture movement is invaluable. One of its greatest strengths lies in its role as a source of local and affordable bulk seed.

For example, Willhite sells a 50-pound bag of common corn seed for $150. Other seed companies may offer the same seed but at $2 to $4 for a small packet. That's fine for the home gardener, but buying the equivalent 50 pounds of corn in seed packs would cost more than $5,000.

Willhite is not just a seed seller, taking bulk seed and packaging it for retail. It's also a seed producer, responsible for developing 40 varieties of melons that have met demand throughout the world.

The company began with the sale of 77 pounds of watermelon seed as a home-based business in 1916, and it has stayed in business because it's needed. Its longtime endurance, through the Great Depression and since, has given it a familiarity with small-scale agriculture that can't be replicated.

Willhite's overseer, Don Dobbs, has worked for Willhite for 50 years. His knowledge of farming is vast. He remembers when every family had a garden that provided the majority of what they ate throughout the year.

When he was young, households gathered together on an appointed day to can their harvest for the winter. He remembers what sustainable, local agriculture was before it became an alternative to other forms of agriculture.

The survival of Willhite Seed Company is a reassurance of sorts that the effort of local growers to develop a sustainable system of regionally produced food is neither unattainable nor unprecedented. It may have fallen off the radar because not enough people were aware of what was happening to our food chain. But Willhite was there before that, it's still here now, and I'm glad we're not about to lose that.