The Space Within

Artists explore the seen and unseen in these ambitious Dallas exhibits

Although at first glance their practices seem miles away from one another, there’s a lot that legendary painter Ross Bleckner and emerging artist John Houck have in common.

Both lend their personal histories to their work, both use methodical processes to reveal their truth, layering the revelations they discover in their own unique ways — and both are currently being featured in one-man shows at the Dallas Contemporary (joining the already wildly successful Bruce Weber retrospective).

Emerging in mid-1970s New York, Bleckner has delved into the concepts of loss and memory as he has deconstructed the actual act of painting throughout his storied career. The artist, who as the subject of a 1995 Guggenheim Museum retrospective, has explored everything from the magnified cellular structures of autoimmune diseases to deconstructed landscapes and still lifes.

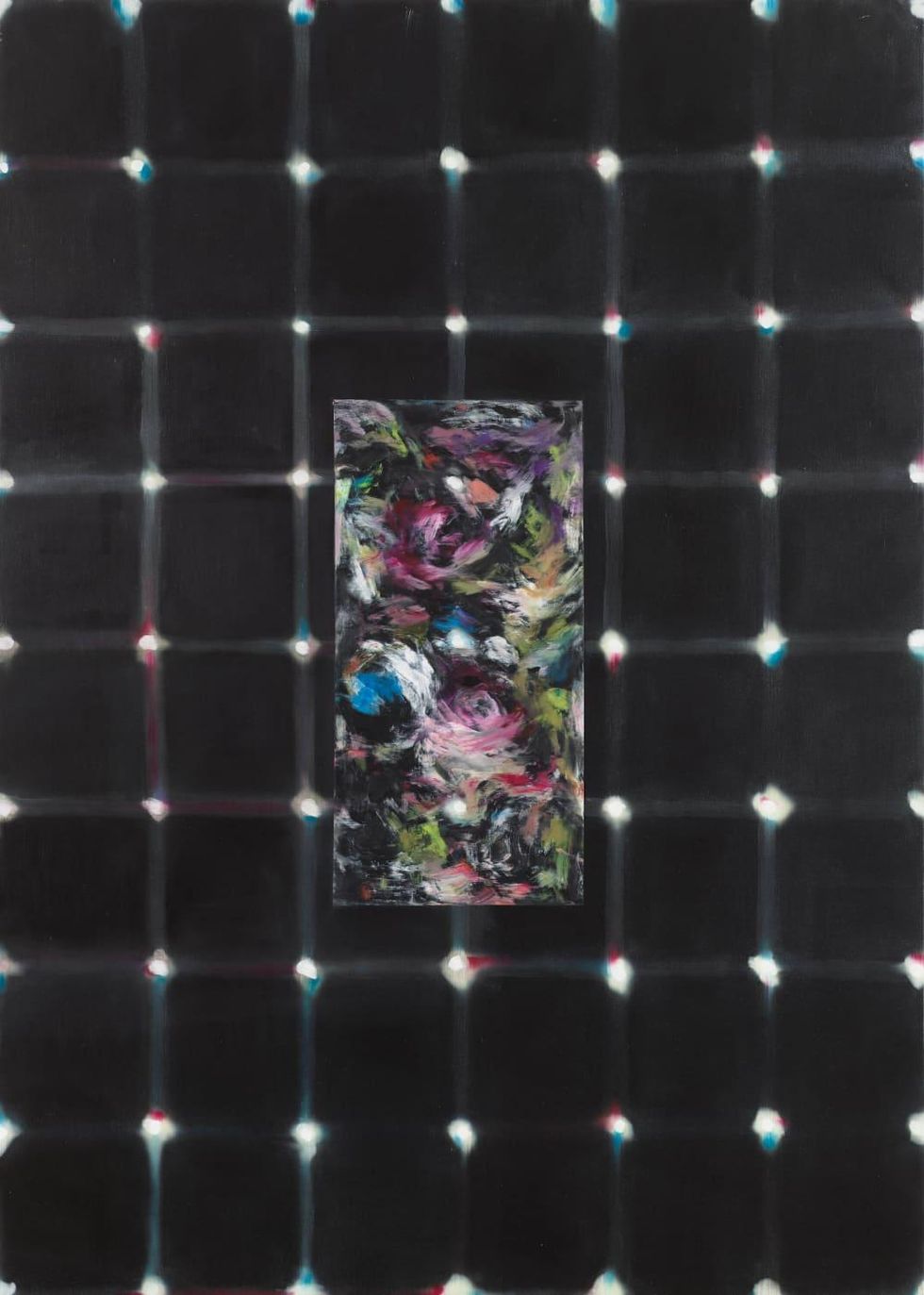

Now, with “Find a peaceful place where you can make plans for the future,” his first major exhibition since that retrospective, the painter refuses to stick to a consistent theme, showing everything from larger-than-life geometric canvases (his Dome series) to blurred-out images inspired by crowds at sporting events.

Clearly illustrative of someone with a lot of ideas he wants to share, Bleckner says “Find a peaceful place” has a “flow of imagery that goes essentially from being very concrete to being dissolved by the end into these kind of landscapes and blurry images of crowd scenes.”

“Just like what’s happening in America now, what’s underneath is coming out,” says Bleckner. “That’s been a trope of mine for a long time. My work has always not really been about nature or landscapes, but about recognition, where things come in and out of clarity — just words and ideas and thoughts and the kind of mixture and complexity that goes on in your own mind.”

Admittedly a “very physical painter,” Bleckner literally scrapes out his incandescent birds or ripening blooms from the backgrounds of his canvases. To him, this process is often more important than what he is actually painting.

“I like that kind of chemistry, and I hope through the mixing of chemicals in a hopefully inventive way something new will emerge that’s not necessarily an image or a metaphor, but an actual physical presence based on the chemistry,” he explains. “I’m actually looking for a change in material.”

Taking a no less heady approach to his work is Los Angeles-based computer-programmer-turned-fine-artist John Houck, who uses a combination of photography and painting to explore the unconscious in his show “The Anthologist.”

Originally attending UCLA for a master’s degree in architecture, Houck was inspired to switch his major to fine art after a meeting with postmodern California artist James Welling.

However, his technical background didn’t disappear entirely — his inventive process of photographing, layering, re-photographing, and finally painting over the final result, lends a surreal quality to his color-saturated images, which belies the meaning of the objects he chooses to capture. Seemingly innocuous items such as a model of a toy ship or a sewing kit actually have an emotional resonance influenced by the artist’s years of psychoanalysis.

“I moved into this body of work using the same process of re-photographing, but I started taking objects my parents had given me over the years,” recalls Houck. “I had started seeing a psychoanalyst and told my parents about this, and it was a big question, like ‘What did we do wrong?’ In addition to talking about it, they started giving me things from my childhood.”

Houck photographed these items, eventually expanding from friends and family to outer members of his social circles in a methodology that mirrored therapy. By using his original image as a backdrop for another shot, the final result has a photoshopped look that also plays with the idea of memory.

“The process of re-photographing is not unlike memory, because memory is a very performative imaginative act,” he explains. “There’s this idea that memory is this objective thing, it’s like pulling up a file in a computer, and it’s the way you left it, but actually every time you remember, it changes slightly over time.”

Like Bleckner, Houck finds fulfillment in the reimagining of material, often painting or drawing his ideas before he sets up a tableau to shoot. With a playful quality, his pieces could also embody the same “sense of the possibility of a kind of sublimity” that Bleckner says he hopes the observer will achieve when standing in front of one of his canvases.

“[It’s about] the ability of painting to transcend our physical being so that you feel like a painting is a moody and thoughtful place, and the viewing is matter of self-reflection,” says Bleckner.

In both of these ambitious exhibitions, there is indeed much more than meets the eye.