The Farmer Diaries

Texas farmer says to hell with freeze and rekindles romance with hydroponics

Now entering my eighth year of trying to grow my own food sustainably, I think I'll focus my efforts on a better approach to food production that will free me from the things that make me hate gardening.

First among my frustrations, there's the watering. My father has installed piping that transports rainwater from our collection tanks to the crops out in the field over 100 yards away, yet still there's so much that can only be watered by my dragging a hose around every day and spending hours just trying to keep the earth under my plants from drying out.

If I add up all the time I spend watering each year, I find that I've sat in my garden with a water hose for about as long as my peers spend on vacation — two solid weeks, 24 hours a day, wasted on routing hydration to plant roots. I hate wasting my time this way. I can get very little else done once the rains end in June. I've resolved that I won't squander another passing precious moment of my life trying to keep my garden from dying, barely.

Anything that can be grown outdoors can be grown hydroponically indoors, and the results are almost always better.

Second, there's the weather. I enjoy growing plants and seeing the fruits of my labor, literally in the colanders full of fresh produce I bring into the kitchen when the climate is just right. But all too often, my efforts are derailed by forces beyond my control, such as last summer's drought that drained my rainwater tanks in mid season and parched the ground under my acres of melons and pumpkins.

Finally the severity of the drought ended. But now in the first half of November, several nights of subfreezing temperatures have claimed every warm season crop in my raised bed garden. The healthy tomato plants that were loaded with green fruit just last week, and the eggplants that promised a little more yield before Thanksgiving, are all just a darkened black mess of plant tissue sprawled out on the ground.

The freeze killed them — and the squash, okra and cucumbers. They weren't old plants, on their last legs and past their prime. They were just entering the height of the productivity. Then came the temperature plunge, and the last holdouts of the 2014 gardening season were dead in a few short hours.

Except for the 20th century invention of chemicals that kill bugs, root out weeds and fertilize soil, little has changed about growing plants for food in the last 10,000 years. My frustrations are nothing new; they're the complaint of countless generations of farmers who have faced the same circumstances. But no more for me.

Last winter I experimented with growing lettuce, a cucumber vine and a couple of tomato plants in a greenhouse. With roots immersed in nutrient-rich water, these hydroponically grown crops bested everything I've ever grown in my organic, raised bed garden. That was phase one of my tests; I used cheap buckets and improvised under-the-bed storage containers to see how hydroponics works.

I'm convinced that indoor farming is for anyone who likes to grow food. It's especially suitable for urban growers.

In phase two, I've gotten serious about year-round vegetable production in a climate-controlled greenhouse. Using Dutch buckets bought from American Hydroponics, a few PVC pipes, a couple of bird bath pumps and common drip irrigation tubing, I've assembled a low-cost hydroponics system that's closer to the quality of a commercial operation.

Now I have a greenhouse full of Dutch buckets with kale, collard greens, Swiss chard and broccoli growing under ideal conditions. Next to them is a row of eggplants, tomatoes and peppers. Coming online by Thanksgiving will be Dutch buckets of squash, various herbs, carrots and whatever else I want to grow.

Anything that can be grown outdoors can be grown hydroponically indoors, and the results are almost always better. What's more, all these plants can be grown year-round, not just in either the spring and summer or the fall and winter.

I chose to grow my indoor crops in Dutch buckets because of all the hydroponics systems, these are the most forgiving; they require much less monitoring of nutrients and pH, especially when a mixture of coconut coir and perlite is used as the soil substitute in the buckets. Coconut coir has so-called buffering capacity, which simply means that like soil, it stores and releases whatever plant roots need rather than the roots being subjected to extreme swings in pH and nutrients that are dripped in.

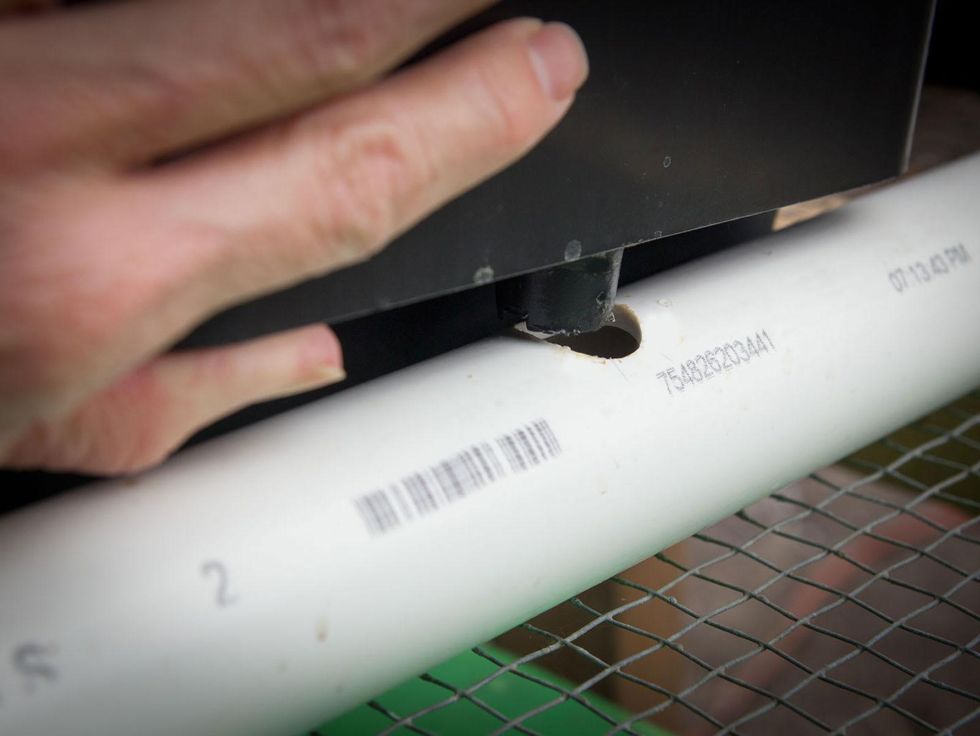

The buckets are made to sit on top of a 1.5-inch PVC pipe. Into the pipe, I drilled half-inch holes, spaced as far apart as I want to space the plants. The buckets have a small outlet near the bottom that fits into the holes I drilled in the PVC pipe. This allows for excess water to drain back to the tank that feeds the drip irrigation tubing in a recirculating, closed loop that wastes no water.

The tank both collects excess water and holds the nutrient-rich solution that's pumped to the drip irrigation so that it can drip into the buckets. A good 460-gallon-per-hour birdbath pump keeps the water flowing. Connected to a timer, the pump only turns on three times per day, 15 minutes at a time. Plants do better when there's time for the roots to breathe for most of the day.

Growing plants hydroponically takes a little getting used to, but once you're up to speed, the effort is minimal.

When the cold front came through last week, I simply fired up the Mr. Heater Big Buddy propane heater in the greenhouse and kept nighttime temperatures in the 60s. The sun heats the interior up to the 90s or above during the day. By opening a window, I try to keep the daytime temperature in the 80s, which is easy to do.

In our latitude, no additional lighting is needed for growing healthy crops in a greenhouse, or even just a high tunnel covered in UV-protected plastic sheeting. The key is to make a structure, however cheap it is, capable of trapping heat and repelling the cold in the winter. In the summer, keeping plants from baking is only a matter of draping a shade cloth over the structure and using an evaporative cooler, low-tech technology that uses just a fan and and water, which cooled homes long before modern air conditioning came along.

I've already begun harvesting kale from my indoor setup, which is why I felt no pressure to cover my outdoor beds this year. The kale is almost sweet, mild and delicately crunchy without a hint of leatheriness that my outdoor kale usually has. Most of all, it has no insect damage, and no blue bugs that seem to invade my greens no matter how cold it gets. I don't know what they are, but they cover my kale each year in the winter and make cleaning it before cooking a chore.

My tomato plants are only three-and-a-half months old, but already they're loading up with green tomatoes. My peppers will take further research, and the eggplants will take some tweaking, but I know I can figure them out. Growing plants hydroponically takes a little getting used to, but once you're up to speed, the effort is minimal. I test the water with a meter, add nutrients or water to keep the levels right, and most of all I just admire my healthy, green thriving plants the likes of which I've never seen in a garden outdoors.

Why I'm doing this has two reasons. For one thing, I'm intent on staying out of the produce section of the grocery store but still eating a healthy diet of leafy greens and other veggies. This has become my preoccupation, my struggle — my obsession.

But after eight years of nursing plants through extreme heat and deadly cold, I've concluded that there's just no sense in putting all the effort it takes into an outdoor garden only to have everything thwarted by foul weather or bugs. I'm convinced that indoor farming is for anyone who likes to grow food. It's especially suitable for urban growers because the yield is far greater in a smaller space than outdoor growing, so small backyard owners rejoice. I can so clearly see a setup like this (dressed up a little) supplying all the herbs at Sundown at Granada, or greens year-round at Garden Cafe, and being a conversation piece on top of that.

But most of all, I want to be a farmer, a real bona fide farmer who makes most if not all his income from the sale of top-quality produce. I've had a taste of this with seasonal melon sales, and my father has made progress with a truckload or two of onions each year.

But to be a full-time grower will take year-round production, and year-round production in a climate prone to heat waves and arctic blasts, happening just weeks from each other, requires a controlled climate and indoor crop production. By building a greenhouse large enough to support a cost-effective crop, my father and I may finally realize our goal of making a living off the land, even if we cover a little of it with translucent panels.