Fracking Fight

Public pleads with city to deny fracking requests

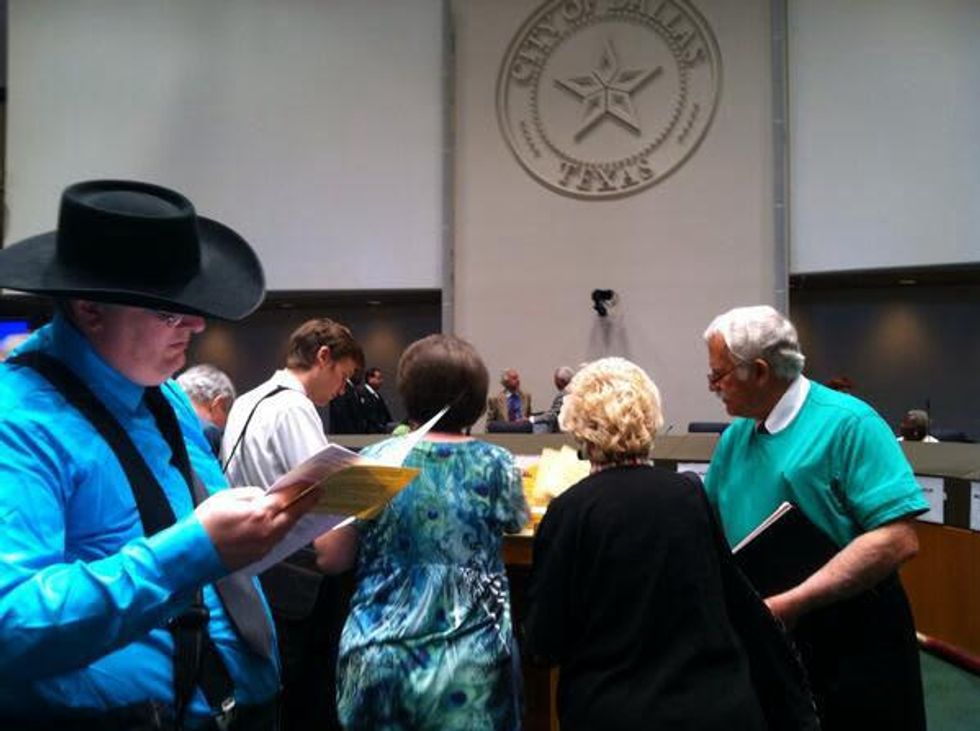

In the latest round of a five-year long game of kick the can, the City of Dallas hosted yet another public hearing August 22 on the possibility of natural gas drilling and hydraulic fracturing. No vote or decision took place; it was merely an open forum for comments.

This time, the point of contention before the City Plan Commission is the setback distance between proposed drilling sites and homes, schools and parks.

Originally, the gas drilling task force recommended a 1,500-foot setback, which the city at first seemed reluctant to accept. However, city staff has since embraced that distance, much to the disappointment of Trinity East Energy. The company believes a setback of that size would effectively ruin their drilling prospects.

"Your agenda isn't setbacks. Your agenda is no drilling," says geologist William Crowder.

In 2008, Trinity East Energy won the right to purchase city land for the eventual purpose of drilling. The two sides have been embroiled in regulatory battles to determine how, when, and if the company will be able to drill on the land it purchased in L.B. Houston Park. Current city code prohibits drilling on parklands and in the floodplain, both terms that describe the land in question.

Around 30 speakers spoke in favor of a 1,500-foot setback and in general opposition to gas drilling, citing concerns of health, pollution and traffic . There were familiar faces, such as Zac Trahan from Texas Campaign for the Environment; Jim Schermbeck from Downwinders at Risk; Gary Stuard from Moveon.org; and Molly Rooke from Sierra Club, but several first-timers also emerged.

In addition to dozens of Dallas residents, opposition came from Carrollton, Garland, Farmers Branch and Fort Worth. "What happens in Dallas, happens in Garland," one woman said before asking the commission to keep the 1,500-foot setback distance in place. Other speakers referenced the documentary Gasland and studies on the correlation to cancer and asthma in patients living near drill sites.

While more than half of the anti-fracking speakers were women, all of those in favor of drilling and against the 1,500-foot setback were men. About a dozen men spoke on behalf of drilling and most tried to debunk the science cited by their opposition.

"Ninety-five percent of these comments are based on bad science," geologist William Crowder said. "It's full of lies. Your agenda isn't setbacks. Your agenda is no drilling."

Crowder went on to address possible legal ramifications of using a 1,500-foot setback. "You have compromised the leases that were purchased," he said. "These leases were not a gift from the city."

Dallas Cothrum, who is representing Trinity East, used a powerpoint to show the limits of such a large setback. He said the restricted distance would be "larger than the SMU campus and Dallas Arboretum combined." Showing an image of Dallas National Golf Course, Cothrum lamented "you maybe could fit one well on there."

Trinity East CEO Tom Blanton expressed disbelief to the commission. "I would urge you to look at the facts and not the unfounded fears you’ve heard this evening," he said, adding that there has not been "one justifiable incident of health and safety" at the thousands of wells fracked in the Barnett Shale.

Another speaker tried to explain the disparity between the two sides. "We don’t have many people out here today because most of them are looking for oil wells so you can put gas in your car and heat in your home," the man said.

Oil and gas attorney Rhodes Hamilton, a partner at Hamilton & Squibb, was the final speaker of the evening. When asked what brought him to the hearing, Hamilton said "just reading, knowing what's out there." He is not currently representing anyone involved in the case, but his opinion is that a 1,500-foot setback is unfair.

"There is an in between somewhere," Hamilton said. "I believe the 1,500-foot setback would be regulation by strangulation."

Trinity East's gas permits are slated to go before the City Council on August 28. Since the City Plan Commission twice denied the permits, the council needs a majority of at least 12 out of 15 members to overturn the commission's decision and grant the permits.