Animal Magnetism

The Guerrilla Girls descend on Dallas to explore the politics of art

Once upon a time, in the brave new art world of the go-go '80s, there existed a wide divide between the work of males and the work of females. This was not due to a lack of talent on the females’ part, but rather a society who automatically assumed that male artists (specifically white male artists) must clearly be superior.

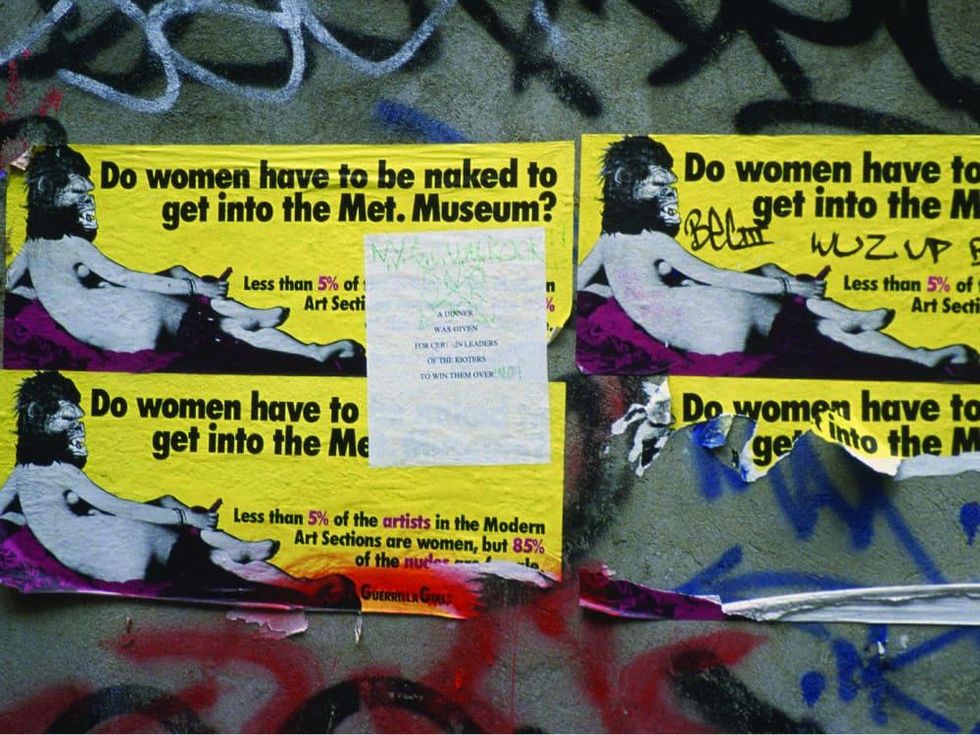

Enter the Guerrilla Girls, a scrappy group of feminine activist artists determined to protest blatant sexism and racism in the art industry. Formed in response to a 1984 Museum of Modern Art survey that showed of the 165 artists featured, fewer than 10 percent were women or minorities, the 1985-founded Guerillas took on the patriarchy with poster art outing misogynist institutions and gallerists. Accidentally called “Gorilla” by a member with a spelling deficiency, these “feminine avengers” took to wearing primate masks to hide their true identities as they fought the system from within.

Over 30 years on, their message — and their mission — has never been more timely or important. The Guerilla Girls will be in Dallas on August 18, for a late-night talk at the Dallas Museum Museum of Art. Guerilla Käthe Kollwitz’s (each member is named after a pioneering, late female artist) was happy to discuss how the more things change, the more they remain the same.

“The face of discrimination has changed in culture in our time, but we have exactly the same strategy [we did when we started],” says Kollwitz, who remains one of the longest-serving members to date, along with her compatriot Frida Kahlo. “But now we try to do it better. It’s basically the idea of twisting an issue around and presenting it in a way that’s never been seen and might have power.”

And always with a dollop of humor. One of their most famous posters — an image of an iconic nude with a monkey mask superimposed over her head — asked, “Do women have to be naked to get into U.S. museums?” An apt question, considering at the time less than 3 percent of the artists in the Metropolitan Museum were women, but 83 percent of its nudes are female.

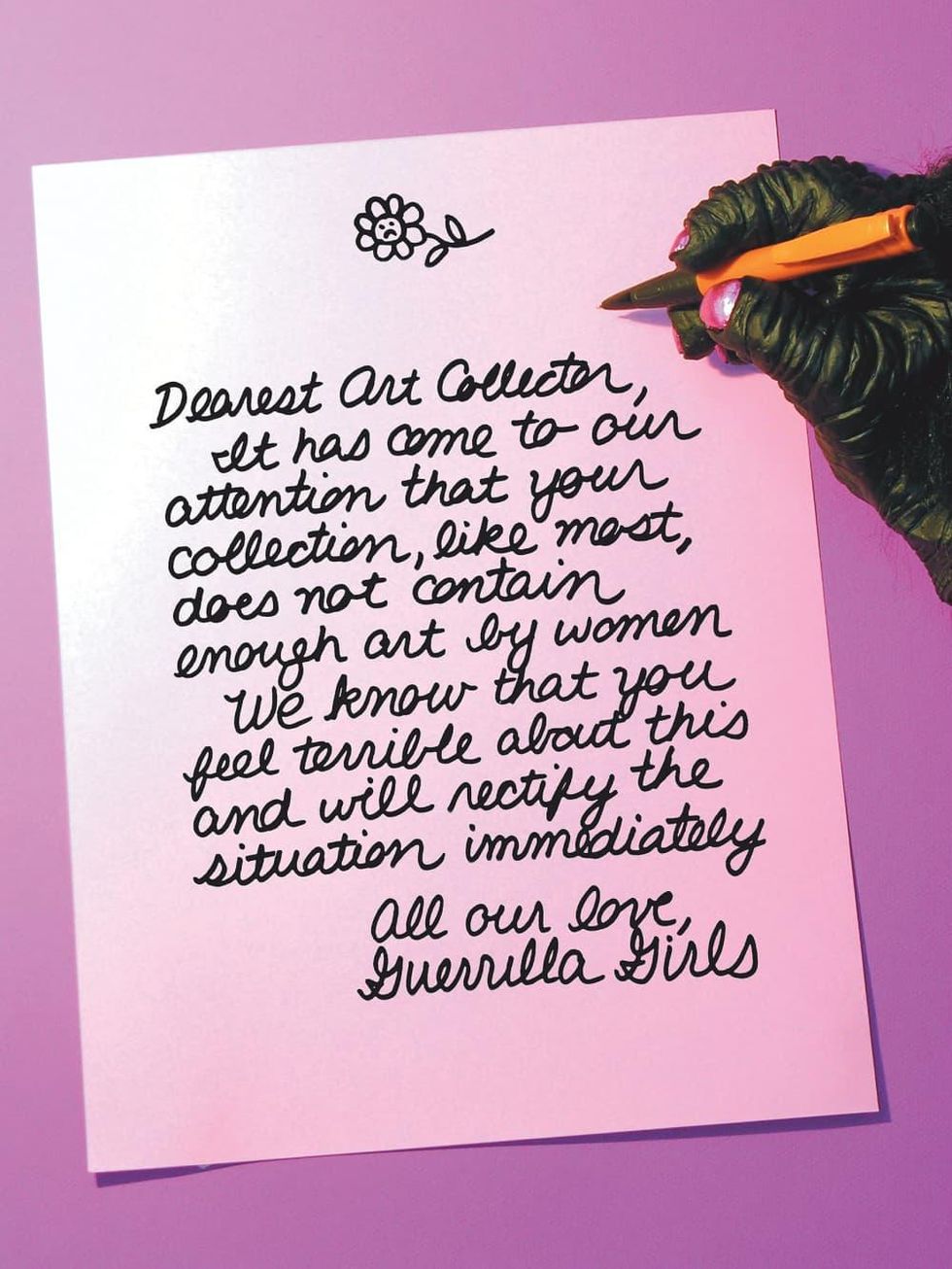

Although the representation of women and minorities has expanded in the ensuing decades, there are plenty of newer problems to prompt concern. Kollwitz says the emergence of super-rich art collectors who donate their very similar stables to museums have helped solidify a limited number of mostly male “art stars.”

“The art world is even more professionalized and multi-national than it was then,” she explains. “When we started out, there were gallery owners that said the work of African Americans did not fit in the gallery system! It’s a little bit better now, but these new forces with big money influences on the art world are a setback.

“We’re in a very difficult time for museums, but there is a bright side, which [is] the curators. There’s so many people in museums that want change.”

Citing the work of Tate Modern director Frances Morris, who brought her museum’s collection up to 30 percent female, as a step in the right direction, the Guerrillas themselves have done much to evolve the system. Now not just protestors of the system, their work is also taken seriously within it.

In 2014, the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired a portfolio of the group’s work from 1985 to 2012, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis has the Guerrillas' entire collection of numbered prints. The National Gallery in Washington, D.C. also owns a few works, which are currently featured at the Dallas Museum of Art’s "Visions of America" exhibition, which closes September 3, 2017.

The group, which has included more than 55 women in its fluctuating membership over the years, has also been unafraid to expand their focus beyond the art world. Protesting everything from the first Iraqi war to Hollywood to the current political administration, there are very few hot buttons they’re afraid to push.

Through their books like Bitches, Bimbos and Ballbreakers: The Guerrilla Girls’ Illustrated Guide to Female Stereotypes and their personal appearances, they hope to continue to raise awareness with a new generation.

“Sometimes we do workshops when we do these gigs — I did a really interesting one after the election at Arizona State,” says Kollwitz. “We show the students how we craft the stuff we craft and how to make political art that can really have an effect on people. They were all terrified to go home for Thanksgiving, but they did a series of placemats so that everyone at [the table] could check whether or not they wanted to talk about the issues.”

Using humor and facts to expose inequity is not only what the Guerrillas have done for 30 years, its what we all can do, every day.

“Things are getting a touch better in art but it’s always two steps forward, one step back," says Kollwitz. "In every area of culture and politics we’ll be busy for a while, but I think everyone will be busy for a while. Speak up!”